Many writers young and old become intrigued and fascinated by another country or another period in history – sometimes both together. This fascination can be triggered by all sorts of different things: travel or living abroad, studying history, reading books, watching cartoons, anime or films, even playing games. Why do we want to write about other cultures? Is it wrong to try to write about cultures different from one’s own? What are the challenges and the dangers?

Why we should do it:

It helps us to understand other nationalities if we try to make an imaginative leap into their world. It certainly casts a new light on our own society. Our own individual writing style benefits enormously from studying the great literature of other cultures, even from the simple act of learning another language.

Why we should not do it:

But it is also a dangerous undertaking, full of pitfalls. It’s harder than you think to rid yourself of your own cultural standpoint and voice. You run the risk of distorting someone else’s culture, patronising it and belittling it. And it is only too easy to introduce anachronisms into a historical setting, both in language and in background. So the whole endeavour needs approaching with great humility and respect – and a lot of hard work.

These are some suggestions on how to set about it:

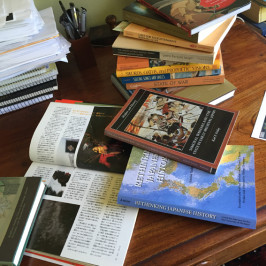

Obviously the first thing is to do your research and to do this you need to know something of the language of the country you are interested in. I can’t stress this strongly enough. For me it’s the essential. You need to be able to read the literature and history of the country in its own language. Sometimes this is extremely difficult – in the case of Japanese for instance. Any effort is better than none. All languages construct and describe the world in a slightly different way: you need to know the idioms and every day speech of your characters, what common symbols mean to them, what their belief system is, and use words that are appropriate. For instance in a culture that does not believe in one Creator God, it makes no sense for one of your characters to say “For God’s sake”. Can alliances be “cemented” in a world that does not build with cement? In a pre-industrial world ideas can’t be electrifying nor can characters be galvanised. You need to look at every word you use and find alternatives for ones that sound too modern.

Not only words, but the objects they stand for. History is many-layered and it’s often not easy to find exactly what you need to know. When were apples introduced into Japan for instance? Or cotton, or candles? I have an illustrated Japanese history book which helps me check on this sort of basic information – clothes, food, crops, armour, weapons and trade.

Other ways to research:

I spend a lot of time looking at pictures and other art works, and watching Japanese movies. Of course, you have to remind yourself that these movies are interpretations of the past that may be only partly accurate and that these pictures may have been painted 200 years after the period you are interested in.

I was lucky enough to receive a grant to travel to Japan from the Asialink Foundation which exists to help Australian artists live and work in Asian countries. But even before I got the grant I had made many trips to Japan to research my books, to walk in the old towns and the countryside, to experience the seasons and the phases of the moon, to listen to the sounds of the forest and the rice fields. I learned about the birds and animals, flowers, shrubs and trees, all the time gleaning details that will help build a world. If you are a writer you need to notice everything, smells, sounds, the pattern of light and shade, the shape of mountains. If you are writing history you need to be able to discern the old landscape beneath the new, where a castle stood at the head of a valley, how people crossed a river before there was a bridge, how the terrain and the weather determine the outcome of a battle. You need all the usual elements of writing, with at least double the effort in research and imagination.

Language:

Much historical writing is spoiled by a lack of awareness of language. Language changes and grows all the time: we speak very differently from people in the past and we use many words that they would never have heard. The writer needs to try and capture or mimic the idiom of the past if writing about English-speaking countries, and invent a style that suggests the speech if it is in another language. I don’t like the convention of using a smattering of words in the language of your chosen country: ie if you are writing about France to have your characters exclaim “Tiens,” “Alors” or “Merci”, or in Japan “sumimasen” or “wakarimashita!” It doesn’t make sense to drop these words into a sentence in English. And often the words themselves are used incorrectly. Better to try to give the flavour of French or Japanese through the subtle use of sentence construction and idioms.

Names:

I spend a lot of time considering names. Readers are very intolerant of difficult or confusing names. Yet to be accurate to my period the names should be quite complex. Also different names were used by family members, and by the outside world. And it was common to change your name from time to time. Whenever I have to choose I usually go for the simpler alternative. So my main characters have short names that are easy to remember.

Time and place:

Days of the week and names of months are very particular to each culture. In pre-modern Japan the year was divided into twelve lunar months, with an extra month added every few years to bring the months back into season. The days were divided into twelve “hours” six between sunrise and sunset, six between sunset and sunrise. So the “hours” were only equal in length at the equinox. There were methods of measuring the passing of time but no clocks and watches as we have, so people were not locked into accounting for minutes or half hours. I try to avoid all such units. Time meant something different then, and so did distance. News travelled only as fast as a galloping horse or a running man.

This brings me to another point:

Make map, charts and calendars of everything you want to put in your book – towns, interiors of houses, the passage of time, the phases of the moon, and of course the overall world. Work out how long it takes to travel across your world, on foot or on horse back, making allowances for bad weather, storms, floods and so on. Are there mountains – you must provide a pass; are there rivers? They will need bridges, fords or transport by boats. You may want to write about armies and battles, but armies need feeding every day so you have to give some thought to who is growing the food and how it is delivered.

Outside help:

I couldn’t have written my books without help from many Japanese friends who checked names for me and helped me with research. If you aren’t sure about something ask for help. There are lots of internet sites now which makes things easier. Be willing to accept that you might have got it wrong and change your writing accordingly. I’m still doing that every day!

3 Responses

» The Art of Unpredictable & Unclassifiable Literature: Writers Discuss Lian Hearn’s Fantasy Epic ‘The Tale of Shikanoko’

[…] that she immerses herself very deeply in research and then tries to leave it behind while writing. This also addresses some of her world-building, especially towards the […]

Jon Winokur

I’d like to interview you via email for AdviceToWriters.com.

Here are the six standard questions:

1. How did you become a writer?

2. Name your writing influences (writers, books, teachers, etc.).

3. When and where do you write?

4. What are you working on now?

5. Have you ever suffered from writer’s block?

6. What’s your advice to new writers?

Plus a brief bio, if you please.

Please let me know if you’re amenable, or if you have any questions.

You can see the previous interviews here: http://www.advicetowriters.com/interviews/.

Thanks,

Jon Winokur

Lian Hearn

Hi Jon, thanks for your message. I’ll send you an email with the answers soon.

Kind regards, Lian