This is the story of the birth of modern Japan, told by Tsuru, a young woman who breaks every stereotype of the Japanese lady. We meet her on the day of her sister’s wedding, and soon realise that she will not accept the same domestic role that her sister is about to take on. Instead, Tsuru is ready to embrace the new world, defend her beliefs, look for love, and follow her career as a doctor working alongside her husband on the battlefields.

In the mid 1860s Japan was in the grip of a revolution almost as tumultuous as the French Revolution 100 years earlier, yet we in the West know very little about it. This book lets readers feel they are there among the revolutionaries, guided by the engaging character of Tsuru. By the end of the first chapter readers will feel they know her, and want to fight with her as she battles against the conventions of the day and falls into a forbidden love. (www.hachette.com.au)

Lian Hearn writes…

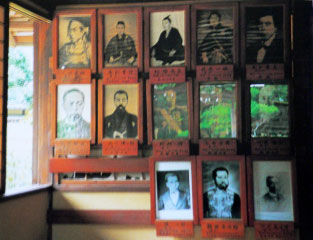

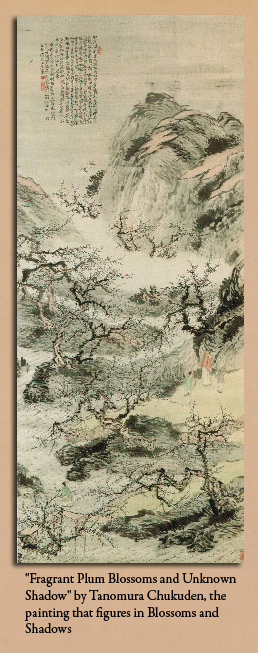

The picture below shows the interior of the Village School Under the Pines, now part of the Shôin Shrine in Hagi, where Yoshida Shoin taught so many of the future Meiji heroes. On the wall are photos of his students: in the top row from the left are Kusaka Genzui and Takasugi Shinsaku, who are among the characters in Blossoms and Shadows. Next is their teacher, Shôin.

When I was in Yamagauchi Prefecture writing Across the Nightingale Floor I was taken by Japanese friends to a tea house in Yamaguchi where conspirators had gathered to plot the overthrow of the Shôgun. Old photos like the ones here lined the walls. There was something about their faces that intrigued me. They wore traditional dress and carried swords, yet were modern enough to have been photographed. As I learned more about them I realised how, while they were still in their twenties, they had brought about changes in their own domain, Chôshû, which had reverberated throughout Japan. I knew little about the Meiji Restoration, but in this rather remote part of Western Japan it still seemed recent history. Takasugi and Kusaka’s houses still existed. The shrine where they played as children seems hardly changed. The huge tengu mask, which scared most children, but not Takasugi, still hangs over the hall. As I learned more about their lives I was amazed that this huge and dramatic event of East Asian history could be so little known in Australia and England.

I decided I was going to try to write about it.

I hadn’t realised how complex, turbulent and contradictory the period known as the bakumatsu (the end of the bakufu) was. It took me years even to begin to unravel the different threads and the competing groups. The idea of writing a novel set in this time seemed utterly beyond me. But the struggle, the sacrifices, the very complexity continued to fascinate me.

Then characters started to appear in my head. In 2002 I spent three months in a small village half way between Hagi and Yamaguchi. I was living in a former doctor’s house, and I began to think about what life would have been like for a doctor’s family in the 1850s and 1860s. Doctors were in small but important ways outside the strict hierarchy of the domain. They had more opportunities for study and travel than most people. And they were in touch with Western ideas through the study of Western medicine. At the end of the Edo period daughters of medical families sometimes worked alongside their fathers and brothers. I decided I would make a girl like this my main character and narrator.

In a way it was a perverse choice. The characters who had sparked my interest were all men. Women played very little part in the narrative of the Meiji Restoration, apart from the inevitable geisha. Yet they were far from invisible in the popular expressions of unrest. Women led religious revivals and took part in the outbreaks of eejanaika. And men and women changed clothes as if trying to break out of their old identities. So my main character, Tsuru, embodies in her life the contradictions, the yearnings, the madness of the times. We see the historical characters through her “half admiring, half exasperated” gaze.

Tsuru narrates the main narrative, but I still felt a need to imagine the inner lives of the historical characters. Their voices spoke strongly to me. So interwoven with Tsuru’s story are glimpses of these men (and one woman, the poet Nomura Bôtôni) at times of crisis, even at the moment of death.

These are the men my story is about.

It is they who broke down the old world and reformed the nation I now live in, with their dreams and delusions, their courage and stupidity, their unexpected successes and their painful failures.

Now they are famous men, those who survived…